The Sublime: Humanity’s Relationship with Nature, From the Renaissance to Romanticism

This is a research paper written for Pioneer Academics during the summer of 2020 under the guidance of Professor Shaneyfelt from Vanderbilt University, nominated for publication in the 2020 Pioneer Research Journal. I wanted to investigate how humanity’s relationship with the natural world was interpreted by Leonardo da Vinci of the Renaissance and Caspar David Friedrich of Romanticism. Because both artists feature sublime natural worlds in their works, I wanted to examine continuities in their interpretations, and the differences arising from a changing society.

Due to the limits of WordPress blog posts, I was unable to upload the proper footnotes present in the research paper on this site. However, all the sources consulted are listed in the bibliography at the bottom of this page. If you would like a PDF of my paper with the proper footnotes and formatting, please email me at [abbyluyuexi@gmail.com].

If you have any comments, suggestions, or questions, please reach out to me! I would love to discuss this with you, or learn from your insights. #Ijustwanttobecomeabetterscholar

Abby Yuexi Lu

Choate Rosemary Hall, Wallingford, CT

Submitted for Pioneer Academics: Summer 2020

The Italian High Renaissance: Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael

Sept 11, 2020

Introduction

The idea of the Sublime as explored in Romanticism—the physical, intellectual, and sentimental grandeur of nature—spans through history to find humanity’s place on Earth. In considering specifically the philosophy of the Sublime as articulated in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgement (1790), it consists of an exploration of the grandeur of the natural world that commands both fear and admiration from the viewer. The Kantian Sublime is a phenomenon experienced when the greatness of the beheld object overwhelms the viewer’s senses and all that can be empirically understood. On the other hand, philosopher Edmund Burke asserted that the Sublime should be an austere reminder of humanity’s triviality in the vast natural world and that there should be no doubt about humanity’s helplessness in front of natural disasters. Artistically, both sides of the Sublime are used during Romanticism as tools to express human sentimentality in exploring the relationship between humanity and nature. Even though the Sublime was established during the Romantic period, we see this interest in the natural world as early as the Renaissance. Despite the different artistic philosophies of both periods, the artists Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519, Renaissance) and Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840, Romanticism) both featured the Sublime landscape extensively in their works.

The Renaissance featured a reinvigorated interest in humanity’s greatness defined by their capability to analyze the natural world empirically. Artists were particularly interested in the depiction of natural forms. In exploring the branching of trees with their leaves, Leonardo da Vinci noted that “the branching of some trees, like the elm, are wide and thin, in the manner of an open hand seen in foreshortening.” In another note, On the Shadow of the Leaf, Leonardo detailed that “a leaf with a concave surface seen in reverse from below sometimes appears half shaded and half transparent.” This methodological approach to painting aligns with contemporary Humanism, which stressed the renewed interest in human subjects and their worth, greatness, and beauty; humans were regarded highly enough to analyze nature.

On the other hand, Romanticism explored an introspective sentimentality. According to contemporary luminaries, notably “in a letter to Friedrich Schlegel dated March, 1801, Ludwig Tieck described Romanticism as ‘… a chaos from which a new certainty must necessarily develop.’” Romanticism was seen by contemporary artists as a time of artistic turmoil from which a certain “truth” of sentimentality evoked by natural scenes was to emerge. The human greatness Romanticism explored was the capacity to feel and empathize with the myriad of experiences of human beings and the overwhelming grandeur of the world’s phenomena, and not the ability to scientifically dissect the world as was the case in the Renaissance. Thus, artwork during Romanticism centered around the natural world.

Leonardo took a scientific approach to art, theorizing the depictions of natural objects. Rather than leveraging sentimentality evoked by certain images, Leonardo focused on the accuracy in replicating the natural image seen by the human eye. In front of a fantastic landscape, however, Leonardo himself often felt amazement and astonishment, but these feelings were usually followed by those of terror and aspiration. In contrast, Friedrich believed that “… a picture should not portray nature itself but only remind us of it. The task of the artist is not to accurately represent air, water, rocks, and trees, but his soul, his sensations, should be mirrored in his artwork.” Friedrich was greatly influenced by natural philosophy in that nature was a physical bible, and also by the idea to worship nature as if it were God itself. Friedrich’s sentimentality extends to his revolutionary visualization of landscape: the landscape full of romantic feeling (die romantische Stimmungslandschaft).

One similarity between Leonardo and Friedrich lies in their common motif of humans in Sublime landscapes, and their exploration of humanity’s place in these cruel and unyielding landscapes. This study will consider four analyses, each focusing on one of Leonardo’s works and one of Friedrich’s, exploring a unique theme connecting the pair of works. The themes are humanity’s life cycle, hope in despondency, nature as a solace, and the sentimentality of pseudo-divinity. These themes show the artistic attempt to understand humanity’s place in this world by striking a balance between two sides of the Sublime: the side that elevates humanity above the natural world, and the side that denies human significance. Comparisons of Leonardo’s and Friedrich’s pieces reveal these common themes, which both artists explore across art history, using the Sublime to demonstrate the equal prominence of humanity and the natural world.

The Life Cycle: Humanity’s Escape from and Connection to Nature

Despite triumphs over nature’s impossibilities, humans are biologically strung to the greater network of living things. This analysis considers the Virgin of the Rocks, by Leonardo da Vinci (1483-86, Figure 1), now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris and The Stages of Life, by Caspar David Friedrich (1835, Figure 2), in the Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig. These pieces were chosen for their depiction of figures in different stages of life in a Sublime background.

In Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks, two women coddle toddlers in the backdrop of an untamed rock structure overrunning with moss and weed. If not for the wings sprouting out from the woman in red’s back unveiling her identity as an angel, these might appear to be ordinary women with their children. The woman in blue hovering between the two toddlers is the Virgin Mary. Despite the angel’s divine status and Mary’s holiness, this grouping resembles a family portrait featuring women and their children. Here, Leonardo does not emphasize the women’s special status, but instead their appeal as accepting mothers. The human life cycle is implied through the figures themselves, from mothers to children. Everybody, regardless of esteem, is subject to the biological connection to nature. However, the women’s saintly statuses suggest a different kind of progression. Life’s cycle is not only represented by childhood, adulthood, and old age, but also as the meek and protected, the protector, and ascension into the realm of God. The landscape is Sublime in its cruel austerity, featuring muted colors and sharp rocks. In a sense, this is analogous to an unrefined human world without the salvation of God. This hostile landscape representing the material world illustrates the idea that life’s cycle is a form of religious salvation.

Friedrich’s The Stages of Life features a typical mortal family: an elderly man, a wife, a husband, and children. In this composition, the Sublime manifests in the sky’s yellow and purple hues, as well as the vast ocean in the background. The colors stratify the sky into succeeding layers, signifying the progression of human life from childhood to middle age to old age, echoed by the figures featured. Additionally, the five ships in the background are, as typical in Friedrich’s works, vessels of life and symbolize his premonition of inevitable death. The two less distinct ships faded on the horizon are the children, the largest boat at the center the father, the boat between the largest and the farthest two the mother, and the one on the far left the old man. Not only do these ships echo the figures’ placements, but also their respective progressions into life, with the one closest to shore representing the old man’s waning life, and the two farthest on the horizon the children’s budding futures. Life’s progression is thus interpreted as proximity to the shore, or the familiar natural world. Once the vessels reach land, they are reduced to mere wood, shown through the rotting raft in the foreground away from the water. Humans, too, are organic matter destined to return to the earth. To this end, the figures are members from three generations of Friedrich’s own family, himself as the old man, the woman as his wife Caroline, the children as his son Gustav Adolf and daughter Agnes Adelheid, and the young man as Friedrich’s nephew Johann Heinrich.

In comparing the two compositions, one can note that both artists explore humanity’s tie to nature through a series of transformations during our lifetimes. Through the common theme of life’s cycle, both artists explore humanity’s connection to nature and the greater web of living beings by featuring humans at various stages of life. Additionally, Friedrich’s inspiration from Leonardo can be seen through the woman’s pointing hand and posture that repeats the body language of the angel, as well as the girl’s pointing hand that echoes that of the Christ Child in the Virgin of the Rocks. However, the works differ in Leonardo’s representation of an alternate life cycle. Through the representation of saints in a typically familial manner in different stages of life, Leonardo suggests the possibility of an alternate cycle of life, one that progresses through stages of religious salvation. In considering the role of the Sublime landscape in both works, Leonardo uses the cave to represent a world from which humans escape, while Friedrich juxtaposes the ships representing humans with the unfamiliar sky and sea. While Leonardo offers hope to escape from the cycle through religious salvation, Friedrich accepts humanity’s ultimate destination: death.

Light in the Dark: Hope in the Midst of Despondency

Because of nature’s cruelty, humans search for transcendental escape from death through desperately seeking light in the midst of darkness. This analysis considers the theme within the paintings of St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness, by Leonardo (1480, Figure 3), now in the Vatican Museums, and The Abbey in the Oakwood, by Friedrich (1809-1810, Figure 4), in the Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin. These pieces were chosen for their despondent landscapes featuring human figures.

In St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness, the emaciated saint appeals to divinity. His mortal body is gaunt and frail, as he is shown when almost a hundred years old. In the painting, Jerome is physically close to death. A sense of despair emanates from his cadaverous physique, which was a result of his devotion in a hermit state, spending his life “dwelling at the Lord’s Crib like a domestic animal” in the holy city of Bethlehem. Jerome’s gestures echo the unbridled emotions of figures in Leonardo’s Last Supper (1498-1500) where figures wallow in despair, appear indignant, and appeal to God. In St. Jerome Praying, the Sublime manifests in the unforgiving landscape speared with jagged rocks in the background cave, which draws a parallel with the cavernous background of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks. Despite the melancholy created by St. Jerome’s physique and the environment, hope shines from the saint’s gaze beyond the picture, to the sky where God resides. The painting thus speaks to the viewer through the saint’s expression. The faintly visible church in the background of the composition emphasizes religion as Jerome’s hope whilst surrounded by despondency.

In Abbey in the Oakwood, the entire picture is awash with darkness and death. The foreground features dilapidated architecture, surrounded by bare oaks with uncannily twisted branches symbolizing a pagan death absent of religious salvation. At the bottom of the composition, a line of monks cast in black walk in a funerary procession. Overall, this landscape both evokes and provokes grief and regret at the dilapidated present following a “golden age.” The decrepit cathedral wall hints at a time when it stood in glory, eliciting a sense of regret at the present stage. Here, the Sublime is manifested in the sheer despondency portrayed through the landscape, in both the lifeless subject matters and monotone color scheme. However, at the bottom of the cathedral wall stands an arch with a cross inside. Two lanterns hang from the sides of the cross, and the monks are walking toward that light. In a landscape defined by death through the bare oaks, tombstones, and dilapidated architecture, the monks walk toward the near light from lanterns hanging off the cross, and the breaking dawn in the distance. This unexpected source of light signifies hope in the midst of death and hopelessness. Here, the distant waxing moon also symbolizes the coming of Christ in the midst of worldly sufferings such as death; the closer light from the lanterns signifies the next step to take to obtain that hope: religious faith. Through practicing religious faith, one can hope to reach the distant and bright light, or eternal life, in the dawning sky illuminated by the moon of God’s light.

A despondent landscape accentuates hope. In both works, the Sublime shows through the surrounding darkness and death. The figure’s aspirations and longings for hope only shine through the austere stone cave of St. Jerome Praying, in which the saint looks to the sky in aspiration for an escape. Likewise, the harsh winter snow in Abbey in the Oakwood shows that despite their impotence, the proceeding figures will continue pursuing a distant hope if it means escape from death. Both paintings explore the idea that despondency is death, and that the only way to eternal life is by following the hope of religious salvation. However, the works differ in their usage of the Sublime landscape. In St. Jerome Praying, the cave representing worldly sufferings, is the source of his despair, and there is no reachable light in sight. Hope is abstract and exists only in faith, while contrasted with hopeless surroundings. In Abbey in the Oakwood, the lights of the distant sky and moon offer a tangible hope, suggesting the dual nature of the Sublime landscape as a source of both hope and despair. Hope only exists when juxtaposed with despair. Regardless of tangibility, without these Sublime landscapes serving as the source of human despair, hope does not exist.

Solace in Nature: Humanity’s Destination of Respite

Even though nature embodies humanity’s despair such as death and the loss of purpose, its religious symbolism also makes it humanity’s solace. This analysis considers the paintings The Annunciation to the Virgin, by Leonardo (1472, Figure 5), in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence and Evening Star by Friedrich (1830, Figure 6), at the Goethe House, Frankfurt. These pieces were chosen for their representation of nature as a comfort for humans.

Throughout life, humans embark on a journey in search of the final solace in an unforgiving natural world, which ironically becomes humanity’s solace. In Leonardo’s The Annunciation to the Virgin, the port tucked away in the background landscape suggests that solace can be found even in the harshest environments; even the harshest landscapes are sources of solace because as a part of nature, they are God’s inventions just like humans. Here, Leonardo’s scientific analysis of natural objects, such as the flowers of the garden in the foreground provides a sense of harmonious unity and formality. In the immediate presence of divine figures, nature becomes tame, in contrast to the wild mountain landscape of the background. Leonardo’s penchant for scientific accuracy also results in every plant pictured having its counterpart in reality. Mary symbolically represents the port of humanity, a resting place for all wandering souls. The ancient name for the virgin is Our Lady, Star of the Sea, a beacon in the vast sea guiding lost souls to the realm of God. The trinity of the port in the distance, Mary’s comforting presence, and religious salvation will be humanity’s final solace in this journey through life, or the natural world.

In Friedrich’s Evening Star, a man rejoices at the sight of a church in the distance, with only its steeple visible through the rolling hills. This composition brims with hope and echoes the central figure’s rapture at having caught sight of a nearby town after covering an impossible span of cultivated farmland, or ecstasy upon religious enlightenment. The figure is surrounded by the distant silhouettes of three church steeples and one cathedral dome, suggesting ecstasy resulted from finally reaching the light, wisdom, and civilization of God, or religious salvation. Here, we see the motif of discovering religious sanctuary in nature, as seen in Friedrich’s other works, Cross in the Mountains (1808) and Morning in the Giant Mountains (1810-1811), in the form of a crucifix. Specifically, the radical directness of the divine natural world in Cross in the Mountains was met with dissent and approbation. The Sublime manifests in the colors of the sky: a dusk awash with a bright yellow. This bright yellow patch of sky further alludes to religious salvation and enlightenment, the serendipitous discovery of human traces in an extensive stretch of natural land. Even though the field the figures are crossing is likely farmland, its vastness suggests the fatigue of traversing it; thus, it is equivalent to worldly affairs that wear out one’s soul. Solace in nature is the trace of civilization in a vast landscape, symbolizing the permanent solace of religious salvation in a sea of worldly affairs.

Nature is humanity’s ultimate solace despite its cruelty. The duality of the natural world serves as a reminder to follow God’s path. Both works portray nature in a comforting light, with human subjects under religious protection. In The Annunciation, the distant port tucked away in a Sublime mountain landscape as the backdrop to a religious scene suggests that in a Sublime landscape and by extension, the material world, there is solace all around if one believes in God. The ecstatic figure reaching a distant church in Evening Star suggests a serendipitous encounter to solace in the form of religious faith. One difference between the works lies in their expression of solace. In The Annunciation, religious solace is modest and formal, from the ceremonial pose of the figures to the ordered garden in the background, suggesting solace in nature is available only through staunch belief. However, in Evening Star, the formality of religion melts away to rapture at having discovered this comfort in a wild field, or the long and tedious journey to salvation. Both artists suggest that just like the process of religious salvation, nature is humanity’s ultimate solace despite the apparent hardships.

Sentimentality: The Glorification of Humanity vs. The Untamed Natural World

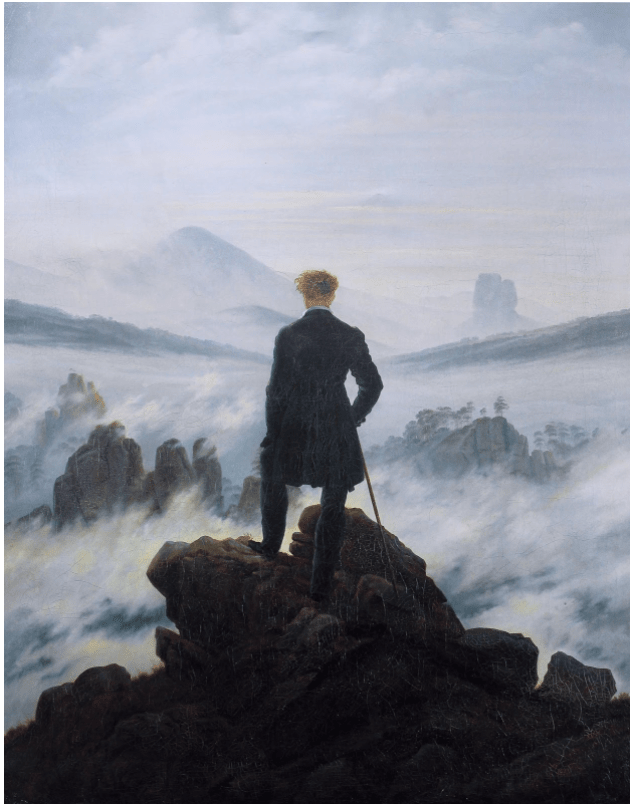

When juxtaposed with a Sublime natural world, human sentimentality manifests in the anthropocentricity of humanity by placing both humans and nature on the same pedestal and recognizing humanity’s insignificance when faced with the untamed natural world. This analysis considers the Mona Lisa by Leonardo (1503, Figure 7), at the Louvre and Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Friedrich (1818, Figure 8), in the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg. These pieces were chosen for their focus on human subjects and their reactions to a Sublime scenery.

Despite being a mere mortal, the young woman (Lisa di Antonio Maria Gherardini, “La Gioconda”) featured in the Mona Lisa seems divine. She is depicted with the same confidence and pride as Leonardo’s image of Jesus in the Salvator Mundi (1490-1500), with the same hazy smile and symmetrical facial features. The fact that both paintings feature a single person means that both figures’ prominent size in the compositions are nearly identical, raising the human onto the same pedestal as God, glorifying the former to the state of pseudo-divinity. Lisa’s knowing smile brims with confidence, and viewers look up to her from our perspectives of psychological triviality. The treacherous and Sublime landscape behind her, God’s masterpiece, is dimmed when compared to her human beauty, as Lisa’s commanding attitude places her high above them. Despite consisting of menacing cliffs, the landscape features mountains, plains, rivers, and a lake. Scientifically, the background is the ideal landscape for life to thrive, and reminiscent of the Garden of Eden in the Bible. Lisa’s face features rare scientific symmetry, absent of wrinkles. By juxtaposing the perfect young woman with a scientifically and religiously perfect landscape, Leonardo elevates her status to that rivalling God’s greatest creations; Lisa, the mortal woman, becomes pseudo-divine.

In Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, Friedrich explores humanity’s comparatively dimmed role in nature through juxtaposing the two. Humans are no longer mere staffage (figures in landscape that are not the primary subjects) in front of an imposing landscape, but instead confront it in full consciousness. Friedrich sets the viewpoint behind the figure, projecting the viewer’s alter ego onto the man’s contemplative form as just a small presence in front of nature. Despite his formal attire and commanding pose, humans are overridden with sentimentality when faced with the Sublime nature, where clouds and mist roll like waves of the ocean. The rolling clouds are reminiscent of both the sky and the ocean, suggesting the idea of a “united natural world,” where the sea of clouds embodies the all-encompassing natural world itself. The figure is believed to be a portrayal of the colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken of the Saxon infantry, who died in the Napoleonic wars, or a civilized hero and the epitome of contemporary human civilization. Faced with an unnavigable landscape, the figure stands at an impasse, unable to continue with his exploration by navigating the sea of fog with a boat, or marching forward on his feet. Even the most competent humans are humbled in front of the natural world, as it cannot be conquered.

Humans are both esteemed and insignificant when compared to the natural world. Friedrich’s portrayal of the natural world echoes similar characteristics seen in Leonardo’s works: the rock formation in the foreground recalls Leonardo’s depiction of stone, the sea of mists are comparable to the sfumato (smoky haze) employed by the Renaissance artist, and the rolling clouds resembling Leonardo’s drawings of deluges, blurring the line between the sky and the sea. Additionally, in the juxtaposition of figures in a Sublime landscape, both Leonardo and Friedrich portray humanity’s sentimentality as the cause of its fluctuating status in nature. Because human emotions are fickle and easily influenced, they soar as high as pseudo-divinity and drop as low as insignificance. In the Mona Lisa, Lisa is exalted even in a divine landscape, as her confidence comes from her very identity as a sentimental human, representing the height of human esteem. In Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, even the most acclaimed individuals fade in front of nature’s glory, representing the low of human esteem. One difference in the exploration of human significance is that in the Mona Lisa, humanity’s meaning comes from the self, while in Wanderer above a Sea of Fog, esteem comes through juxtaposition with the magnificent natural world. Humans draw sentimentality from nature, and the assessment of humanity’s value comes from fluctuating emotions.

Conclusion

Despite the different philosophies of their respective periods, the works of both Leonardo da Vinci and Caspar David Friedrich have shown that humans and nature are equal through exploring the common theme of the Sublime. Through placing human figures in Sublime landscapes, the artists have shown that humans hold equal prominence as nature in this world. The analysis of Virgin of the Rocks and The Stages of Life shows that humanity is inextricably linked to nature by our biological life cycle, which can be transformed by religious salvation. Initially, this seems like eternal condemnation to follow nature’s cycle, but this chain can be broken by the human choice to follow religion. The artists depict desolate landscapes as foils to hope found in the prospect of religious salvation in St. Jerome Praying in the Wilderness and The Abbey in the Oakwood. Without the austere landscapes, hope cannot shine through. Therefore, humanity needs nature’s cruelty to fully experience the salvation of hope. Even with its portrayal as a cruel and unforgiving force, the natural world along with all its intimidations is humanity’s solace, as seen through the comparison of The Annunciation to the Virgin and Evening Star. By living in the Sublime world and drawing sentimentality from its greatness, humanity’s place in the world fluctuates between pseudo-divinity in the Mona Lisa and triviality in Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog. These highs and lows in human introspection show the ever-changing dynamic between people and nature. Together, these four themes illustrate Leonardo’s and Friedrich’s respective understanding of humanity’s place in the natural world. The fluctuating status of humanity’s role in nature results in the ultimate balance between the two.

Our equal relationship with nature strikes a delicate balance, but modern humans challenge this balance by attempting to conquer nature and become divine to the point of hubris. The nascence of Romanticism itself was to remind humans of the importance of nature in the face of the industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century. Despite the equivalent and inseparable relationship humanity shares with nature, we are becoming increasingly detached from it with advancements in technology, which chips steadily away at this balance. As humanity nears the brink of hubris while rampaging through the natural world’s resources, we must look back on works of art for lessons to be learnt, and be careful not to emulate Icarus, the son of Daedalus in Greek mythology whose pomposity became his downfall. Throughout history, humanity is reminded to respect the natural world, as a faction within its vast web of life things, not to dominate it. In doing so, humans encounter something beyond themselves: the Sublime.

Bibliography

Amstutz, Nina. “Caspar David Friedrich and the Aesthetics of Community.” Studies in Romanticism 54, no. 4 (2015): 447-75. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.choate.edu/stable/43973932.

Bailey, Colin. J., Author, and Clive. D. Field, Editor. “Religious Symbolism in Caspar David Friedrich.” 71, no.3. https://doi.org/10.2307/community.28212345.

Barolsky, Paul. “‘Mona Lisa’ Explained.” Source: Notes in the History of Art 13, no. 2 (1994): 15-16. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.choate.edu/stable/23205051.

Barolsky, Paul. “The Paradox of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks.'” Source: Notes in the History of Art 18, no. 4 (1999): 16-18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23206809.

Beenken, Hermann. “Caspar David Friedrich.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 72, no. 421 (1938): 171-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/867281.

Börsch-Supan, Helmut. “Caspar David Friedrich’s Landscapes with Self-Portraits.” The Burlington Magazine 114, no. 834 (1972): 620-30. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.choate.edu/stable/877126.

Brady, Emily. “Reassessing Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature in the Kantian Sublime.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 46, no. 1 (Spring 2012). https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.46.1.0091.

Bambach, Carmen C. Leonardo Da Vinci, Master Draftsman. Edited by Carmen C. Bambach. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003.

De Girolami Cheney, Liana. “Leonardo Da Vinci’s Uffizi Annunciation: The Holy Spirit.” Artibus Et Historiae 32, no. 63 (2011): 39-53. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.choate.edu/stable/41479736.

Emison, Patricia. “Leonardo’s Landscape in the ‘Virgin of the Rocks.'” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 56, no. 1 (1993): 116-18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1482664.

Leonardo, da Vinci, Leonardo on Painting: An Anthology of Writings by Leonardo Da Vinci with a Selection of Documents Relating to His Career as an Artist. Compiled by Martin Kemp. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Miesel, Victor H. “Philipp Otto Runge, Caspar David Friedrich and Romantic Nationalism.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin 33, no. 3 (1972): 37-51. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.choate.edu/stable/40514139.

Mitchell, Timothy F. “From Vedute to Vision: The Importance of Popular Imagery in Friedrich’s Development of Romantic Landscape Painting.” The Art Bulletin 64, no. 3 (1982): 414-24. https://doi.org/10.2307/3050244.

Modiano, Raimonda. “Humanism and the Comic Sublime: From Kant to Friedrich Theodor Vischer.” Studies in Romanticism 26, no. 2 (1987): 231-44. https://doi.org/10.2307/25600649.

Vine, Steve. “Blake’s Material Sublime.” Studies in Romanticism 41, no. 2 (2002): 237-57. https://doi.org/10.2307/25601558.

Illustrations

Figure 1. Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks, ca. 1483-1486, Louvre, Paris.

Figure 2. Caspar David Friedrich, The Stages of Life, ca. 1835, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig.

Figure 3. Leonardo da Vinci, Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, ca. 1480, Vatican Museums, Rome.

Figure 4. Caspar David Friedrich, The Abbey in the Oakwood, ca.1809-1810, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Figure 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Annunciation, ca. 1472, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 6. Caspar David Friedrich, Evening Star, ca. 1830, Goethe House, Frankfurt.

Figure 7. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, ca. 1503-1506, Louvre Museum, Paris.

Figure 8. Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, ca. 1818, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg.